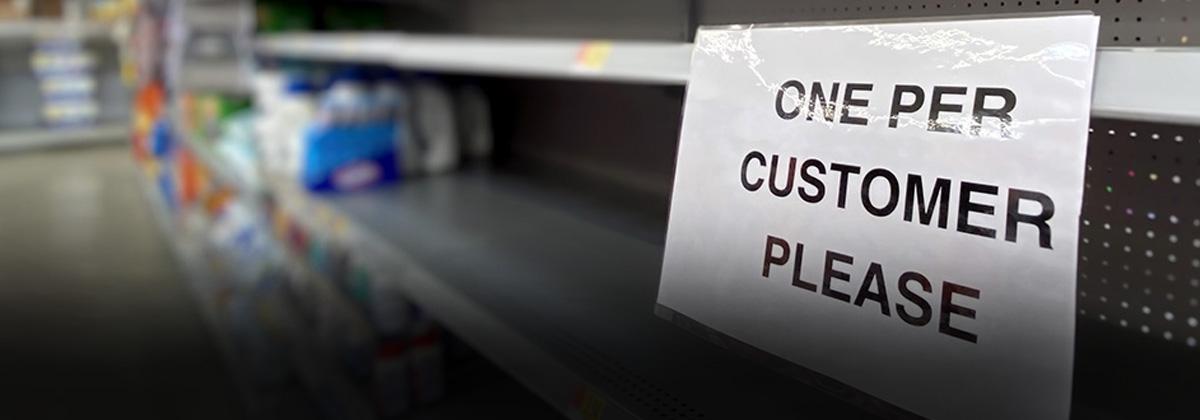

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, many businesses were unprepared to deal with the impact on their operations. We look at the lessons to be learned and what you can do to prepare for future events.

It’s often said that no one could have foreseen the COVID-19 pandemic. While the exact nature of the virus may not have been predicted, there had been plenty of warning about the potential for a pandemic of some sort to occur.

So why did people ignore the warnings? Analysis by Interactive Investor shows that only 13 of the UK’s FTSE 100 companies included the risk of a global pandemic in their 2020 business plans despite warnings as far back as 2016.

It’s hard to get businesses to invest in measures to mitigate high impact, low probability events. The Health and Safety Executive sums it up like this: “Every day, consciously or unconsciously, we all view hazards and evaluate their risks to determine which ones we choose to notice, ignore or perhaps do something about.

“We may take the consequences of some risks for granted and, for others, consider that our own chances of being harmed may be either more or less than the average, depending on the apparent degree of control we have for taking or limiting the risks.”

Of course, threats don’t have to be global to bring your operations to a halt. The breakdown of a critical machine could be enough to stop production. Everyday risks like fires, extreme weather and civil disruption can also impact your operation.

“In the melee of something having just happened, people tend to be like headless chickens, it is a natural reaction and a plan is something to anchor on.”Ian Bell, Vice President of Engineering and Facilities, RS Group

Ian Bell, Vice President of Engineering and Facilities at RS Group emphasises the importance of having a plan to deal with major incidents. “It is absolutely essential, if for nothing else, to give some structure early on,” he says.

“Because in the melee of something having just happened, people tend to be like headless chickens, it is a natural reaction and a plan is something to anchor on.”

It’s essential to keep your plan clear and straightforward, he says. “Where a lot of companies go wrong is trying to over-engineer the plans. They make them too specific to individual scenarios and hope that it gives every answer. The trouble is, every scenario is different.”

A survival toolbox

A fire in the staff kitchen is very different from a major fire that destroys the roof of the factory, he adds. Rather than categorising risks under broad headings, it makes more sense to build what he calls a toolbox of actions and responses.

“Give yourself software contingencies or additional equipment that you can roll out,” he says. “Create a communication plan so you can keep people informed and identify an emergency team structure to coordinate your response.

“Don’t link your tools to specific scenarios because you’ll need to evaluate your situation and then go to your toolbox and roll them out. But make sure any of the tools you come up with actually work in the real world.”

When disaster strikes, Bell says the first step is to secure what has survived the incident and get a clear picture of how things stand. “In this situation the immediate desire is to start fixing things, but what we need to do is secure and understand it,” he adds.

Gary Harvey, Head of UK Field Services at RS, says site design is critical to surviving an incident. “While many businesses have a business interruption procedure – and that’s very useful and really important – it hasn’t often been considered when designing a site in order to prevent some of these things from happening,” he says.

“It’s important but I think the majority of manufacturing industries, frankly, don’t take it seriously . And they think, sometimes correctly, that the problems they’re going to get are so rare that it’s not worth investing in.”

“These are often referred to as low probability, high consequence events. I’m not convinced that they’re low probability – they seem to be coming around far too frequently for my liking.”Dr Moray Kidd, Maintenance Engineering Academic

Maintenance Engineering Academic Dr Moray Kidd is not so sure that attitude is tenable. “These are often referred to as low probability, high consequence events,” he says. “I’m not convinced that they’re low probability – they seem to be coming around far too frequently for my liking.”

Analysing risk

A planning tool often used in maintenance engineering is “bowtie analysis”, he explains. “It’s called bowtie because on the left we consider the causes that might lead to a disaster; in the middle we have the disaster itself; and on the right we have the consequences.

“It’s a technique that we often use to communicate risk and it’s a really effective way of all the stakeholders thinking about their role in keeping people, the environment and the business safe.

The Royal Academy of Engineering says one of the key lessons of the pandemic was the importance of stocking critical spare parts and ensuring your supply chains are robust.

Identifying pinch points and critical elements of your supply chain is an essential part of resilience planning, says the Academy. It’s also important to identify supplies that can be sourced locally and where buffer stocks may be needed.

Richard Jeffers, Managing Director of RS Industria at RS Group, suggests this checklist to help you evaluate the resilience of your maintenance engineering processes in the event of an incident:

1. Do you have a maintenance strategy? If you don’t, you need one, even if it’s quite simple and straightforward.

2. How strong is your maintenance plan? Is everyone following it day to day?

3. What’s your plan based on? Is it the manufacturer’s recommended service intervals or do you use data from monitoring your assets to create a predictive maintenance plan?

4. Are you making the most of fault reporting to understand where the weaknesses exist in your set-up?

5. Do you have a disaster recovery plan? Have you read it? Is it actionable?

6. Have you thought about what you would be able to do in reality if the worst happened ?

7. Do you know which are your critical assets, the ones that will stop the factory or cause a compliance issue?

“There’s no doubt in my mind that if you are performing world-class maintenance engineering, which is about the relentless identification and eradication of losses, you are setting yourself up to survive a crisis,” says Richard Jeffers.

A plan for continued production

As Dr Moray Kidd points out, severe events, which in the past we’ve regarded as unlikely to happen, seem to be occurring more frequently. Just hoping for the best won’t cut it anymore. Maintenance engineering needs robust plans to ensure it is prepared to keep production running, whatever may occur.

For information on support RS can provide, please visit RS Maintenance Solutions here.